We are the guardians of a unique heritage of history, beauty, taste, experience and passion, which we have a duty to safeguard and pass on intact to the next generations.

Its history, since 1763

The story began back in 1763, when the acquacedratario (citron drink-maker) Giuseppe Dentis opened a small shop in the building facing the entrance to the Sanctuary of the Consolata. At the time, the place was modestly furnished with wooden tables and benches. The current building was designed by the architect Carlo Promis and constructed in 1856. It is where the coffeehouse took on its modern-day elegant demeanour: the walls were embellished with wooden panelling decorated with mirrors and lamps and the characteristic small round white marble tables, the wooden and marble counter and the shelves for the confetti jars appeared. At the end of the nineteenth century came the front window with its metal frame, glass side windows and cast iron columns and capitals. It is where the confectionery and coffeehouse business took place.

The success of the café was without doubt founded on the invention of the bicerin, however, rather than an invention, it was an evolution of the eighteenth-century bavareisa, a fashionable drink at the time that was served in large glasses and made using coffee, chocolate, milk and syrup. At the beginning, the ritual of the bicerin saw the three ingredients served separately, but as early as the nineteenth century they were poured into a single glass and were available in three variations: “pur e fiur” (similar to today’s cappuccino), “pur e barba” (coffee and chocolate) and “’n poc ‘d tut” (“a little bit of everything”), with all three ingredients. The latter variation was the most successful and ended up overshadowing the others and making it, unaltered, to our time, taking the name from the small glasses without handles in which it was served (the bicerin). The drink also became popular in other coffee bars in the city, even becoming one of the symbols of Turin.

The success of the café was without doubt founded on the invention of the bicerin, however, rather than an invention, it was an evolution of the eighteenth-century bavareisa, a fashionable drink at the time that was served in large glasses and made using coffee, chocolate, milk and syrup. At the beginning, the ritual of the bicerin saw the three ingredients served separately, but as early as the nineteenth century they were poured into a single glass and were available in three variations: “pur e fiur” (similar to today’s cappuccino), “pur e barba” (coffee and chocolate) and “’n poc ‘d tut” (“a little bit of everything”), with all three ingredients. The latter variation was the most successful and ended up overshadowing the others and making it, unaltered, to our time, taking the name from the small glasses without handles in which it was served (the bicerin). The drink also became popular in other coffee bars in the city, even becoming one of the symbols of Turin.

The history of the Bicerin, which was how the Turinese came to call the café thanks to the success of its drink, became closely interwoven with that of the “Consolà” with the passing of time. Indeed, the new mixture was the ideal pick-me-up for the faithful who, having fasted to prepare for Holy Communion, needed energy as soon as they came out of the church. Likewise, it was very popular during Lent because hot chocolate was not considered “food”, so it could be consumed with a clean conscience when fasting.

The history of the Bicerin, which was how the Turinese came to call the café thanks to the success of its drink, became closely interwoven with that of the “Consolà” with the passing of time. Indeed, the new mixture was the ideal pick-me-up for the faithful who, having fasted to prepare for Holy Communion, needed energy as soon as they came out of the church. Likewise, it was very popular during Lent because hot chocolate was not considered “food”, so it could be consumed with a clean conscience when fasting.

The Museo Torino (the City of Turin’s virtual museum) possesses very detailed information, including historical research, on the Caffè Al Bicerin.

The café was also involved in the Risorgimento and the Unity of Italy, thanks to Camillo Benso di Cavour. It is said that the Count, who was liberal, secular and anti-clerical, would wait for for the royal family to leave the sanctuary, instead of accompanying them, sat comfortably at the table under the clock, checking the entrance of the Consolata from behind the curtains.

The café was also involved in the Risorgimento and the Unity of Italy, thanks to Camillo Benso di Cavour. It is said that the Count, who was liberal, secular and anti-clerical, would wait for for the royal family to leave the sanctuary, instead of accompanying them, sat comfortably at the table under the clock, checking the entrance of the Consolata from behind the curtains.

Female management

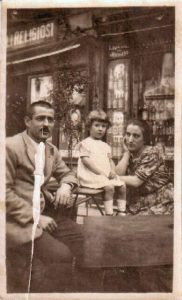

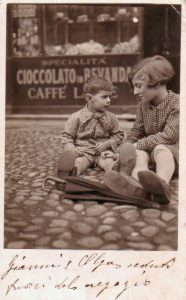

At one time, the cafés were run the exclusive preserve of men: men would meet there to drink, smoke and chat. “Respectable” women could not go to places that were so unsuited to them. The Bicerin soon proved to be a unique in this regard, too: it had been opened by a man, but its management soon fell into the hands of ladies. Its unique position facing the Sanctuary of the Consolata made it a favourite destination for female customers, who felt safe and at ease in its particular environment, the specialties served were typical of a chocolate-confectionery establishment and the alcohol served was just vermouth, rosolio and ratafià. For many years, it was one of the few places in which women could be seen on their own in public; they would dip butter biscuits in a bicerin to break the fast after the services at the sanctuary. The fact that it was run by women made it suitable for ladies. This characteristic gave the place a gentle and delicate feel that is true to this day. From 1917 to 1971, the coffee bar was run by Mrs Ida Cavalli, with the help of her sister and daughter Olga, then, from 1972 to 1977 it was run by Mrs Silvia Cavallera. The Cavalli ladies were much loved and well-known throughout the city: more ladies of the house than coffee bar owners, they lovingly looked after all the penniless intellectuals who took shelter from the bitter cold in the Caffè Al Bicerin.

At one time, the cafés were run the exclusive preserve of men: men would meet there to drink, smoke and chat. “Respectable” women could not go to places that were so unsuited to them. The Bicerin soon proved to be a unique in this regard, too: it had been opened by a man, but its management soon fell into the hands of ladies. Its unique position facing the Sanctuary of the Consolata made it a favourite destination for female customers, who felt safe and at ease in its particular environment, the specialties served were typical of a chocolate-confectionery establishment and the alcohol served was just vermouth, rosolio and ratafià. For many years, it was one of the few places in which women could be seen on their own in public; they would dip butter biscuits in a bicerin to break the fast after the services at the sanctuary. The fact that it was run by women made it suitable for ladies. This characteristic gave the place a gentle and delicate feel that is true to this day. From 1917 to 1971, the coffee bar was run by Mrs Ida Cavalli, with the help of her sister and daughter Olga, then, from 1972 to 1977 it was run by Mrs Silvia Cavallera. The Cavalli ladies were much loved and well-known throughout the city: more ladies of the house than coffee bar owners, they lovingly looked after all the penniless intellectuals who took shelter from the bitter cold in the Caffè Al Bicerin.

Maritè

In 1983, Maritè Costa inherited the legacy of the Cavalli ladies, taking the coffee bar to the level of international notoriety for which it is now known. She performed an extraordinary task of true archaeology of Turinese chocolate and sweets: the research and study of original recipes, quality materials and a real and authentic love for traditional Piedmontese chocolate and pastries resulted in the small coffee bar becoming known and loved throughout the world. A number of awards soon began to arrive, in particular one from the prestigious Gambero Rosso magazine, which nominated the Caffè Al Bicerin the “Best Bar in Italy” in the first edition in 2001. As well as the great care and attention paid to the quality and the tradition of food, Marité added passion for the preservation of the historic environment, a true icon of the city, beginning a full-scale restoration of the original structures and furnishings. This was done to preserve the atmosphere and hospitality of nineteenth century Turinese chocolate establishments. Her approach to hospitality has become a true institution in the city, which culminated in her receiving the 2013 Bogianen Award in recognition of 30 years of work in the business.

In 1983, Maritè Costa inherited the legacy of the Cavalli ladies, taking the coffee bar to the level of international notoriety for which it is now known. She performed an extraordinary task of true archaeology of Turinese chocolate and sweets: the research and study of original recipes, quality materials and a real and authentic love for traditional Piedmontese chocolate and pastries resulted in the small coffee bar becoming known and loved throughout the world. A number of awards soon began to arrive, in particular one from the prestigious Gambero Rosso magazine, which nominated the Caffè Al Bicerin the “Best Bar in Italy” in the first edition in 2001. As well as the great care and attention paid to the quality and the tradition of food, Marité added passion for the preservation of the historic environment, a true icon of the city, beginning a full-scale restoration of the original structures and furnishings. This was done to preserve the atmosphere and hospitality of nineteenth century Turinese chocolate establishments. Her approach to hospitality has become a true institution in the city, which culminated in her receiving the 2013 Bogianen Award in recognition of 30 years of work in the business.

After Maritè passed away in 2015, the establishment continues to be proudly managed in the traditional manner by our family, with the help of the ladies who have been working at the coffee bar for years.